Tough Times Don’t Last But Tough Startups Do

(this article was featured in this WSJ article)

I closed my eyes and counted to three while in an empty and dark conference room. I told myself that I was ready to tell my friend and coworker that I would be laying him off. I needed to shut off my emotions. I needed to close the valve on my feelings, and close it tight. I opened my eyes, and walked downstairs. I tap my friend on the shoulder, “Can we talk?”, and we move into another conference room. Tim, our CEO, is already in the room, ready to co-pilot the meeting with me. I close the door tightly. The three of us sit in a distanced triangle. There is a long pause.

“I need to tell you something important.”

I present the details that need to be presented: The reasons, the timeline, how long benefits will last, severance, next steps. I’ve seen Tim do this before, and I’ve been the co-pilot. It is much easier to be the co-pilot. All you have to do is pay attention and fill in any gaps that you notice. This time, I’m driving. I am making eye contact, fully aware because of the adrenaline. At the same time, distant because of what I told myself in the dark conference room. I dutifully complete the agenda.

“Out of all people, I would have expected you to be more empathetic about this.” says my friend.

All of a sudden, I realize how deeply offensive I must seem to him, to be so cold. Suddenly, the valve in my heart twists open, and all of the feelings start flooding out: The disappointment, the guilt, the anger, and sadness. My eyes begin to water and my throat closes up. I try to speak, but can’t. I hoarsely force a couple words out, but stop mid-sentence. Tim notices, and picks up from where I am stuck, and the meeting continues. How did it get to this?

FUNDRAISING COMMITTEE

On August 24, 2015, the TINT Fundraising Committee was formed to decide on whether or not we should fundraise or to continue to bootstrap our own growth. In the traditional TINT fashion, we democratically elected a 7 person committee, and set up regular weekly meetings. Just one month before in July, we had closed our biggest deal yet.

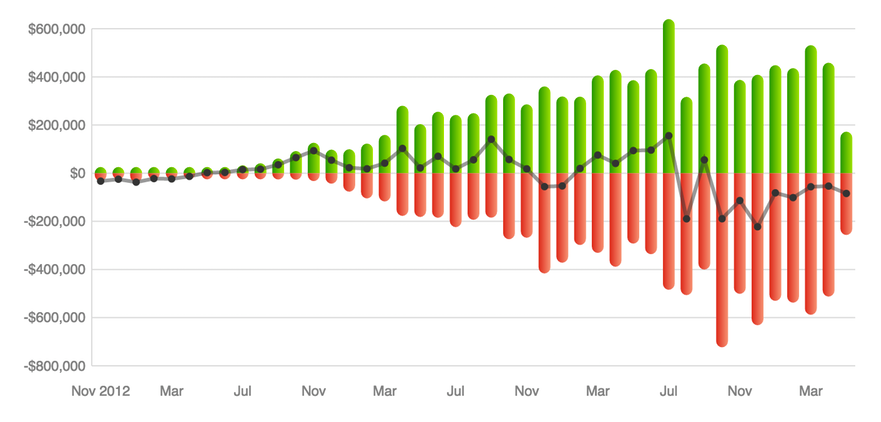

One of our largest clients wanted to display their social media using TINT, and they committed $120k+ to us. We felt like the world was our oyster as we watched the monthly revenue soar to a spectacular $640k for that month, a huge difference from the previous highest revenue month of $432k.

The committee met weekly for the month of September, and developed a financial model to predict how aggressively we could spend, and when we could start seeing returns from our spending. After much back and forth, the committee coalesced around a single model that highlighted everything from a hiring model to our sales cycle. The model suggested that if we hired aggressively, we would be able to expect to see equally aggressive revenue growth after the negative effects of the slow winter season ended. The model also suggested that we would be able to stay safe even without outside funding.

Based on these suggestions, on October 7th, the committee sent out an email to the team. TINT would “delay fundraising and pursue a course of creating a relatively more aggressive hiring/spending plan. This plan will be focused on driving revenue growth over the next 6 months and measuring the incremental impact of marketing and outbound sales on our revenue as well as increased product and operational expenses.”

However, the committee was not completely blind to the risks. The email from the committee continues: “Admitted Risk: We realize there is a chance that increasing our spend could lead us to no longer being profitable and being forced to fundraise in a situation where we are burning cash in 2016. This is a calculated risk we are taking based on our projections which show we will not end up in a situation with significant burn. Excited to put some gas on the fire and prove out some of our growth assumptions!”

On December 3rd, 2015, we still felt that we were on track, and the committee sent out an update: “I am happy to say that we are overall exceeding our goal, despite being slightly below numbers for November.” The email told the team to anticipate 10 hires before next April.

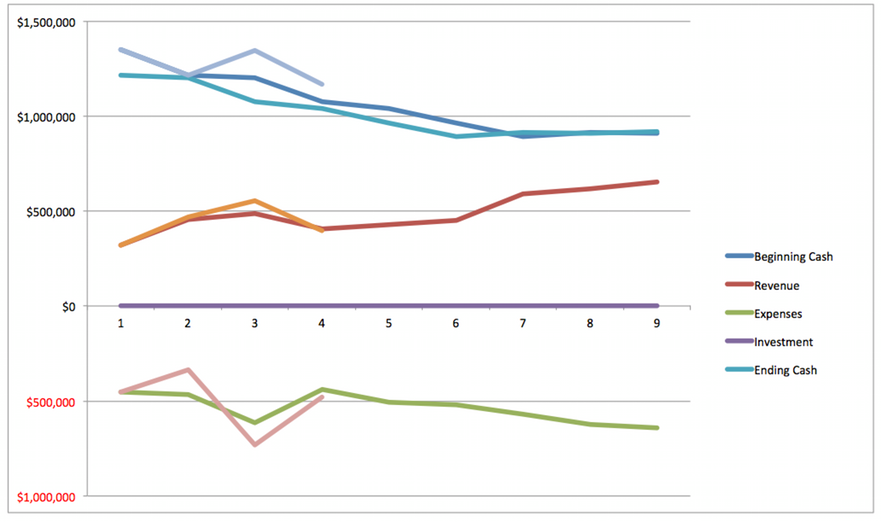

The graph below shows what we saw when that email was sent. According to the plan, we were still on track. The X-axis is set up such that “4” represents November. On closer examination, you will notice that the revenue line (red) jumps up significantly at 7, 8, and 9, which represent February, March, and April. That’s when we’d start to see the returns from our investment. The model predicted that during those months we would see revenue climb to 580, 620, and 650. We could do it right? We did it in July!

GAS ON THE FIRE

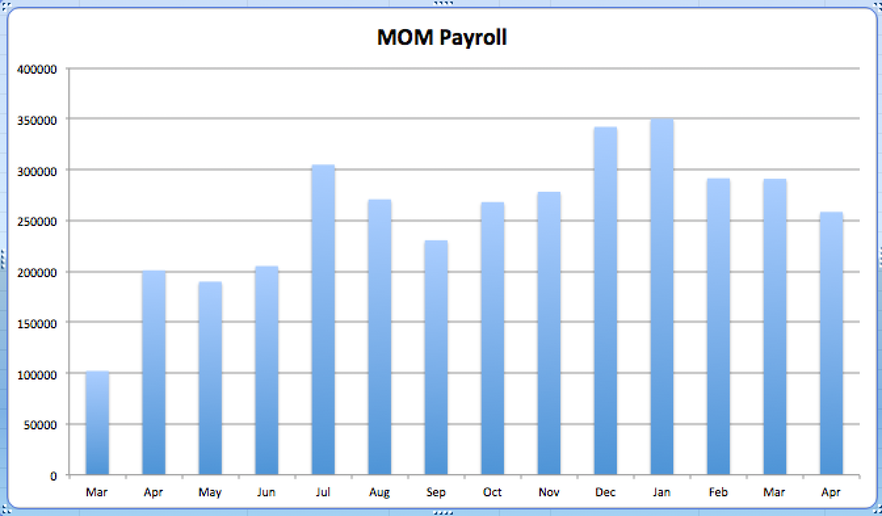

From September 2015 through February of 2016, we brought on 11 full time employees. 4 of them were international and were previously contracting. Before the growth plan, from April through September, payroll averaged at $234k. From September through February, payroll averaged $293k, growing a whopping $60k.

In addition, we upgraded our digs. We went from paying $8.5k on a 3000 square foot office to paying $35k on a 10000 square foot office. Total office related expenditures climbed from a $28k in January to $62k in February. The cost of moving offices was even worse than we anticipated because we were not able to find a sublessor for the old office. Given the bullish office real estate market in San Francisco, we expected to make a healthy profit of 8k from our old office. Instead, we were experiencing an 8.5k loss, as we continued to lower the price each month, desperate for a company to move in. Ouch.

COMING TO A HEAD

In January, we hit our target of $450k. However, the good news did not last long. In February, we missed the 580 target significantly, and only made $436k. By the middle of March, it was clear that we were not going to hit $620k, and it was becoming increasingly obvious that we would not hit $650k as predicted in April. If we were to project more conservative revenue expectations forward, our bank account would look dangerously low.

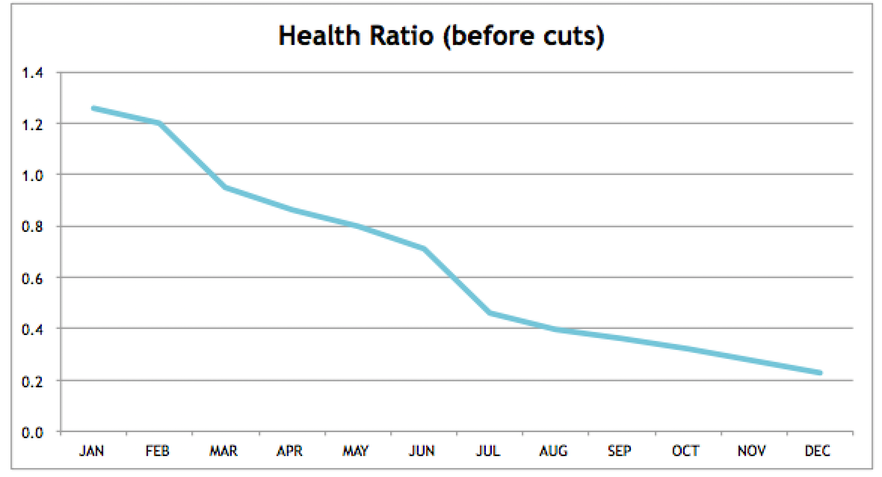

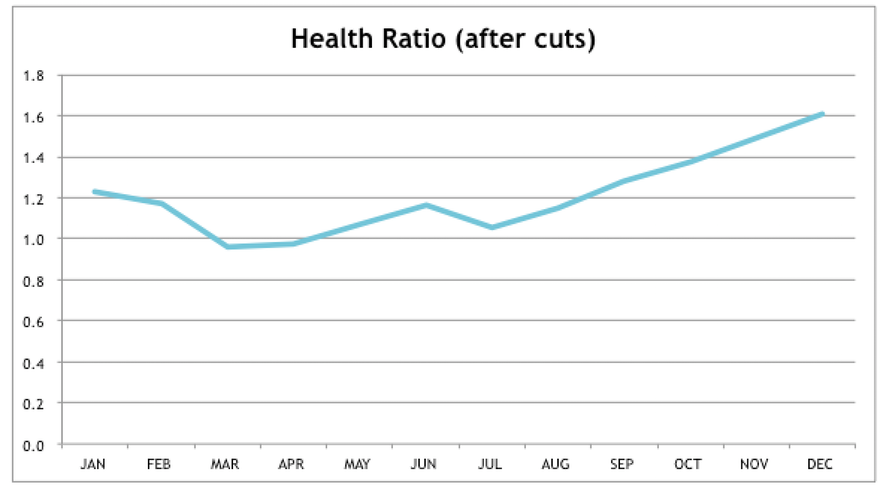

How low? Well, let’s take a look at the projected health ratio. The health ratio is a number that represents the general health of the business and is simply the business’ bank balance divided by monthly core expenses. Anywhere below 1.0 is dangerous for the business, because once you dip below that, it is possible to not make payroll if revenue for that month does not arrive in time. The projection showed that our health ratio would dip to an alarming 0.6 by the middle of the year, and by the end of the year we would be bankrupt. Simply put, the model put us in an existential crisis. Compounding the necessity to make a decision was a team retreat that was scheduled for the beginning of April. If we were going to make drastic cuts, it would be best to make them before the all hands team retreat.

The day things came to a head was March 23, 2016. It was decided that afternoon among the co-founders that emergency planning would need to take place, and the co-founders met for extended periods between the 23rd to the 27th, scrambling on Saturday and Sunday to come up with a plan to both reduce expenses and to effectively communicate the reductions to the team. The two plans we needed to decide between were to either Cut Shallow or Cut Deep. The Cut Shallow plan involved cutting around $30k in expenses, and then working on immediately raising a $1-2M buffer round of funding. The Cut Deep plan involved cutting $50k in expenses, and then working on reaching profitability before considering raising money. After debate, we decided to go with the Cut Deep plan because it reduced the chances of a second cut, which would be devastating to morale and our long term growth. From there, we worked to make the impossible decision of which employees would be cut. Ultimately, it was a decision that was based on what would make the least drastic impact to the business.

The decision making process was brutal and ugly. It felt awful. It involved putting everyone’s name on the board and going through them one by one, and going through the impact each person would make on the business if they were laid off. After getting through the list, we went through the list again. And then we went through the list yet again, one last, painful time. Each time, we pushed back against each other when we disagreed and identified areas where we needed to collect more information. We wished we had the experience to be able to make an optimal call. Given the constraints given to us, we did the best we could, but we still walked away disappointed that employees would have to be cut for the mistakes that we had made as the leadership team.

Stakeholders were called in the weekend before the announcement to individually meet with the cofounders. They included some early employees, and continuing employees that would be affected the most. The cofounders shared the components of the plan that applied to them, so that they could gather feedback and to prepare them for Monday. By Sunday night the cofounders had a deck, a timeline, and a sleepless night ahead.

THE LAYOFFS

On Monday, March 28, the co-founders proceeded with the layoffs, scheduling meetings with the applicable employees in hour long calendar events whose sole agenda was to let them know what was happening and to deliver the necessary details. The announcement to the team was scheduled for noon. Unfortunately, the last layoff meeting went longer than expected, and Tim had to deliver the news to the team alone without Ryo and Nik. Tim walked the team through the deck. It explained the necessity to make big expense reductions, restructure the company, and implement new processes.

After the presentation, employees were largely in shock. With a number of missing threads, the social fabric of the team was frayed, and walking through the office it could be felt. Adding to the tumultuous day, one of our top performing salespeople announced her resignation shortly after the presentation. It was by coincidence: She had planned on making her announcement on that day the week before, not knowing about the layoff.

THE AFTERMATH

It was only in the weeks afterward, that we began to realize the mistakes we had made when communicating the layoffs to the team. The biggest mistake we made was that we confused the difference between a firing and a layoff, which are legally very, very different. Inadvertently, we had created an HR liability for our company, and upon learning this mistake, we immediately worked to make clear that this was a layoff, not a firing. Another mistake we made was that we did not announce who was being laid off in the team announcement, until someone asked for it. That was really the only question on everyone’s mind, and it was against our values to not share it immediately. Yet another mistake we made was not looping in our Operations Manager and HR team before the announcement. This would likely have prevented the other mistakes.

On March 30, just 2 days after the announcement, the team set off for Wonder Valley in Fresno for the team retreat. We usually have a retreat every 6 months to strategize and bond. This time, it would be to repair. Our Operations Manager did a wonderful job of planning the retreat for the past couple months, and the retreat proceeded without incident, smoothly and efficiently. We paddled canoes, brainstormed Q2 strategies, and played cards late into the night. However, even the best retreat would not be able to fully heal the wounds left from losing one’s friends from the workplace. The team came back from Fresno closer than they were after the announcement, but still fragmented, and feeling the weird energy the layoffs brought about.

In April and May we saw a continuation of the aftermath when 2 key engineers announced their resignation in order to pursue their own interests. This hit the team particularly hard because both of these employees represented strong talent on the team.

That brings us to the present. Today, we are still working to handle the situation day by day, leading initiatives to get back to profitability. Until we reach a stable financial state, we will be operating in a mode of scarcity, holding off promotions and our 401k matching program. The scarcity is a painful but important motivator in absorbing the lessons learned.

LESSONS LEARNED / LEARNING

- Expect the best, but plan for the worst – We expected the best, and planned for the best. At each step of the way, we leaned on the optimistic side. Our aggressive hiring plan assumed that we would be able to source quality candidates in that time, even though past data showed that it takes months to find a quality candidate. Our office plan assumed that we would be making a big profit from subletting the space. The growth plan projected very, very optimistic revenue growth. We should not have baked as much optimism into our plans.

- Cut Deep, Cut Once – This was the first word of advice from almost every advisor, mentor, and online resource we consulted before making the decision. Leadership only has one chance to convince the team that the company can be turned around.

- Fundraising – Fundraising should be guided by an individual who has the most experience in fundraising. For us, that person was Allen Morgan, a member of our board, who should have been brought into the discussion much earlier. Instead, he was informed at the beginning of 2016, months after the committee laid the groundwork for the growth plan.

- HR – We learned that a firing and a layoff are very different, even if both are based on performance. In the future, we will talk to an HR professional before making big moves.

- Motivation – After making the announcement, morale was at a historic low. The co-founders felt pressure to motivate the team. However, how do you motivate a team that’s just gone through a round of layoffs? What we learned from our sales advisor Bridget Gleason, was “You can’t motivate people – it’s not your job to motivate people – your job is to provide a great environment where motivated people can be successful”. We learned not to beat ourselves up for everyone feeling awful, and to be patient and focus on what is under our control to create a successful environment moving forward.

- Doing More with Less – In the months after the layoff, we asked ourselves more and more “What does success look like?” Instead of taking a “spray and pray” approach to our activities, we now spend more time tracking impact so that we can learn how we can do more with less. You can only improve what you can measure.

THE FUTURE

Although we experienced the largest setback in this company’s history, we must remember everyday to appreciate how far we have come. We are making steady revenue from a group of passionate customers and have a product that regularly sells itself. The comments our customers give us for our easy to use product and personal customer service is inspiring.

We have overcome challenges in the past. Depression, burnout, breakups, and surviving on the bare minimum with only 3 months of runway left. Each challenge larger and more daunting than the one before. But each time, we have improved ourselves and developed solutions to move forward.

We are now 2 months past the layoffs, and are experimenting with new ways of approaching work. Here is how we are challenging ourselves to improve:

- Data – In the past, we never got around to measuring what we wanted to know. Now, when we start a project, we are more disciplined about asking ourselves, “What does success look like?” We are more careful about measuring our results and more disciplined about learning from our mistakes. More analysis means faster failing, more learning, and a higher chance we’ll work on what will make the most difference for our customers.

- Goals – In the past, we took a scattershot approach to what everyone was working on and didn’t provide adequate direction or coordination. We set goals, but they were often forgotten by the middle of the quarter. Now, we have improved how we create goals, spending more time making sure that they are the right size and have strong business value. Also, we have made our goals more visible by adding them to our 1:1 process. By keeping us focused on our long term objectives, we will be able to achieve more with less.

- Restructuring – Previously, we had 7 department heads for an organization of about 30. This resulted in significant overhead in coordinating all of the heads. We are now dividing up management responsibilities among the 3 co-founders and our sales director, which results in less communication overhead, and more time to focus on customer needs.

As for what the future holds, much is beyond our control: Competitors continue to leave and enter the space, the market evolves at a rapid pace, and customers’ needs change. However, I believe the future is still in our hands. The best team is going to write the best software, sell the best pitch, generate the greatest following.

We are not the typical VC-funded Silicon Valley company. Because we are self-sustaining, we have the luxury of focusing on sustainable growth. And we have an excellent team at TINT, to move us forward on that path. We feel the pressure, but it makes us stronger. Next time, we’ll be more careful about putting gas on the fire.